| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Biliary Atresia |

|

|

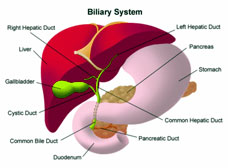

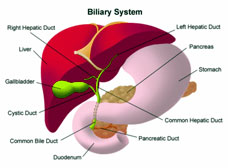

What is biliary atresia?

Biliary atresia is a serious but rare disease of the

liver that affects newborn infants. It occurs in about one in

10,000 children and is more common in girls than in boys and in

Asian and African-American newborns than in Caucasian newborns.

The cause of biliary atresia is not known, and treatments are only

partially successful.

The liver damage incurred from biliary atresia is caused by injury

and loss (atresia) of the bile ducts that are responsible for

draining bile from the liver. Bile is made by the liver and passes

through the bile ducts and into the intestines where it helps

digest food, fats, and cholesterol. The loss of bile ducts causes

bile to remain in the liver. When bile builds up it can damage the

liver, causing scarring and loss of liver tissue. Eventually the

liver will not be able to work properly and cirrhosis will occur.

Once the liver fails, a liver transplant becomes necessary.

Biliary atresia can lead to liver failure and the need for liver

transplant within the first 1 to 2 years of life.

What are the symptoms of biliary atresia?

The first sign of biliary atresia is jaundice, which causes a

yellow color to the skin and to the whites of the eyes. Jaundice

is caused by the liver not removing bilirubin, a yellow pigment

from the blood. Ordinarily, bilirubin is taken up by the liver and

released into the bile. However, blockage of the bile ducts causes

bilirubin and other elements of bile to build up in the blood.

Jaundice may be difficult for parents and even doctors to detect.

Many healthy newborns have mild jaundice during the first 1 to 2

weeks of life due to immaturity of the liver. This normal type of

jaundice disappears by the second or third week of life, whereas

the jaundice of biliary atresia deepens. Newborns with jaundice

after 2 weeks of life should be taken to the doctor to check for a

possible liver problem.

Other signs of jaundice are a darkening of the urine and a

lightening in the color of bowel movements. The urine darkens from

the high levels of bilirubin in the blood spilling over into the

urine, while stool lightens from a lack of bilirubin reaching the

intestines. Pale, grey, or white bowel movements after 2 weeks of

age are probably the most reliable sign of a liver problem and

should prompt a visit to the doctor.

What causes biliary atresia?

The cause of biliary atresia is not known. The two types of

biliary atresia appear to be a “fetal” form, which arises during

fetal life and is present at the time of birth, and a “perinatal”

form, which is more typical and does not become evident until the

second to fourth week of life. Some children, particularly those

with the fetal form of biliary atresia, often have other birth

defects in the heart, spleen, or intestines.

An important fact is that biliary atresia is not an inherited

disease. Cases of biliary atresia do not run in families;

identical twins have been born with only one child having the

disease. Biliary atresia is most likely caused by an event

occurring during fetal life or around the time of birth.

Possibilities for the “triggering” event may include one or a

combination of the following factors:

* infection with a virus or bacterium

* a problem with the immune system

* an abnormal bile component

* an error in development of the liver and bile ducts

Research on the cause of biliary atresia is of great importance.

Progress in the management and prevention of biliary atresia can

only come from a better understanding of its cause or causes.

How is it diagnosed?

Worsening jaundice during the first month of life means a liver

problem is present. The specific diagnosis of biliary atresia

requires blood and x-ray tests, and sometimes a liver biopsy. If

biliary atresia is suspected, the newborn is usually referred to a

specialist such as

* a pediatric gastroenterologist who is an expert in digestive

diseases of children

* a pediatric hepatologist who is an expert in liver disease of

children

* a pediatric surgeon who specializes in surgery of the liver and

bile ducts

Initial tests. The doctor will press on the baby’s abdomen to

check for an enlarged liver or spleen and order blood, urine, and

stool tests to check for liver problems. The level of bilirubin in

the blood will be measured and special tests for other causes of

liver problems will be done.

Ultrasound of the abdomen and liver. Ultrasound tests produce an

image on a computer screen using sound waves. Ultrasound tests can

show whether the liver or bile ducts are enlarged and whether

tumors or cysts are blocking the flow of bile. An ultrasound

cannot be used to make a diagnosis of biliary atresia, but it does

help rule out other common causes of jaundice.

Liver scans. Liver scans are special types of x rays that use

substances that can be detected by cameras to create an image of

the liver and bile ducts. One such test is called hepatobiliary

iminodiacetic acid (HIDA) scanning. HIDA scans trace the path of

bile in the body and can show whether bile flow is blocked.

Liver biopsy. If another medical problem is not found to be the

cause of jaundice, a liver biopsy may be recommended. For a liver

biopsy, the infant is sedated and a needle is passed through the

skin and then quickly in and out of the liver. A small piece of

liver, about the size of a pencil lead, is obtained for

examination using a microscope. A liver biopsy will usually show

whether biliary atresia is likely. A biopsy can also help rule out

other liver problems, such as hepatitis.

How is it treated?

Surgery. If biliary atresia appears to be the cause of the

jaundice in the newborn, the next step is surgery. At the time of

surgery the bile ducts can be examined and the diagnosis

confirmed. For this procedure, the infant is sedated. While the

infant is asleep, the surgeon makes an incision in the abdomen to

directly examine the liver and bile ducts. If the surgeon confirms

that biliary atresia is the problem, a Kasai procedure will

usually be performed on the spot.

Kasai procedure (hepato-portoenterostomy). If biliary atresia is

the diagnosis, the surgeon generally goes ahead and performs an

operation called the “Kasai procedure,” named after the Japanese

surgeon who developed this operation. In the Kasai procedure, the

bile ducts are removed and a loop of intestine is brought up to

replace the bile ducts and drain the liver. As a result, bile

flows from the small bile ducts straight into the intestine,

bypassing the need for the larger bile ducts completely. (More

about the Kasai procedure follows.)

Liver transplant. If the Kasai procedure is not successful, the

infant usually will need a liver transplant within the first 1 to

2 years of life. Children with the fetal form of biliary atresia

are more likely to need liver transplants—and usually sooner—than

infants with the typical perinatal form. The pattern of the bile

ducts affected and the extent of damage can also influence how

soon a child will need a liver transplant. (More about liver

transplantation follows.)

The Kasai Procedure

The Kasai procedure can restore bile flow and correct many of the

problems of biliary atresia. This operation is usually not a cure

for the condition, although it can have an excellent outcome.

Without this surgery, a child with biliary atresia is unlikely to

live beyond the age of 2. The operation works best if done before

the infant is 90 days old and results are usually better in

younger children.

The improved results of the surgery make the early diagnosis of

biliary atresia very important, preferably before the infant is

several months old and has suffered permanent liver damage. Some

infants with biliary atresia who undergo a successful Kasai

operation are restored to good health and can lead a normal life

without jaundice or major liver problems.

Drawing of the Kasai procedure for biliary atresia. Part of the

small intestine is attached to the liver and replaces the bile

ducts so the liver can drain properly.

The Kasai Procedure

Unfortunately, the Kasai procedure is not always successful. If

bile flow is not restored, the child will likely develop worsening

liver disease and cirrhosis and require liver transplantation

within the first 1 to 2 years of life. In addition, the Kasai

operation, even when initially successful, may not totally restore

normal liver development and function. A child with biliary

atresia may slowly develop cirrhosis and related complications and

require a liver transplant later in childhood.

While the Kasai procedure has been a great advance in the

management of biliary atresia, improvements in the operation and

clinical management of children who undergo it are needed to

improve the outcomes of children with this disease.

Liver Transplantation

Liver transplantation is a highly successful treatment for biliary

atresia and the survival rate after surgery has increased

dramatically in recent years. Children with biliary atresia are

now living into adulthood, some even having children of their own.

Because biliary atresia is not an inherited disease, the children

of survivors of biliary atresia do not have an increased risk of

having it themselves.

Improvements in transplant surgery have also led to a greater

availability of livers for transplantation in children with

biliary atresia. In the past, only livers from small children

could be used for a child with biliary atresia because the size of

the liver had to match. Recently, advanced methods have been

developed to use part of an adult’s liver, called “reduced size”

or “split liver” transplants, for transplant in a child with

biliary atresia.

In addition, surgery has been developed that allows taking part of

a living adult donor’s liver to use for transplantation. Thus,

parents or relatives of children with biliary atresia can donate a

part of their liver for transplantation. Because healthy liver

tissue grows quickly, if a child receives part of a liver from a

living donor, both the donor and the child can grow complete

livers over time.

What happens after surgery?

Both before and after the Kasai procedure, infants will receive a

specific diet with the right mix of nutrients and vitamins in a

form that does not require bile to be absorbed. Poor nutrition can

lead to problems with development, so doctors will monitor an

infant’s nutritional intake closely.

Some infants develop fluid in the abdomen after the Kasai

procedure, which makes the baby’s belly swell. This condition is

called ascites and usually only lasts for a few weeks. If ascites

lasts for more than 6 weeks, cirrhosis is likely present and the

infant will probably require a liver transplant.

Also common after the Kasai procedure is infection in the

remaining bile ducts inside the liver, called cholangitis. Doctors

may prescribe antibiotics to prevent cholangitis or prescribe them

once the infection occurs.

Children with biliary atresia may continue to have liver problems

after the Kasai procedure. Even with success of the operation and

return of bile flow, some children will develop injury and loss of

the small bile ducts inside the liver, which can cause scarring

and cirrhosis.

The liver affected by cirrhosis does not work well and is more

rigid and stiff than a normal liver. As a result, the blood flow

through the liver is slowed and under higher pressure. This

condition is called portal hypertension. Portal hypertension can

also cause flow of blood around, rather than through, the liver.

This complication can cause intestinal bleeding that may require

surgery and may eventually lead to a recommendation for liver

transplantation.

Cirrhosis of the liver can also lead to problems with nutrition,

bruising and bleeding, and itching skin. Itching, called pruritus,

is caused by the build up of bile in the blood and irritation of

nerve endings in the skin. Doctors may prescribe medications for

itching including resins that bind bile in the intestines or

antihistamines that decrease the skin’s sensation of itching.

|

|

|

Growing Stronger, Growing

Better

|

|

| |

|

Global Health |

| |

|

|

health checkup

|

|

Healthcare Provider |

| |

|

|

|

Biliary Atresia - treatment of Biliary Atresia,

Biliary Atresia types, Disease medicines, Biliary Atresia symptoms, Biliary

Atresia and Disease symptoms, Biliary Atresia symptoms Disease and

diagnosis, Symptoms and Solutions, Signs and Symptoms, type of Biliary

Atresia, cause common, common Biliary Atresia, Biliary Atresia List, causes

list, Infectious Biliary Atresia, Causes, Diseases , Types, Prevention,

Treatment and Facts, Biliary Atresia information, Biliary Atresia:

Definition, Biliary Atresia names, medical Biliary Atresia, medical Biliary

Atresia and disorders, cell Biliary Atresia, Biliary Atresia Worldwide,

Biliary Atresia Research, Biliary Atresia Control, Biliary Atresia Center,

Digestive Biliary Atresia Week, Information about Biliary Atresia, causes of

different Biliary Atresia, Biliary Atresia Articles, Biliary Atresia and

conditions, Health and Biliary Atresia, Biliary Atresia Patients, Biliary

Atresia and Sciences, causes of alzheimer's Biliary Atresia, Biliary Atresia

causes, alternative medicine heart Biliary Atresia, body ailments, Biliary

Atresia medicines, medical antiques, type of blood Biliary Atresia |

|

|