|

* Colon anatomy and development

* Malrotation

* Small bowel and colonic intussusception

* Fistulas

* Colonic atresia

* Volvulus

* Imperforate anus

* Hope through research

* Points to remember

* For more information

The colon, or large intestine, is part of the digestive system,

which is a series of organs from the mouth to the anus. When the

shape of the colon or the way it connects to other organs is

abnormal, digestive problems result. Some of these anatomic

problems can occur during embryonic development of the fetus in

the womb and are known as congenital abnormalities. Other problems

develop with age.

Colon Anatomy and Development

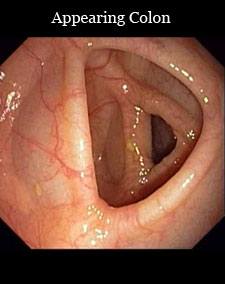

The adult colon is about 5 feet long. It connects to the small

bowel, which is also known as the small intestine. The major

functions of the colon are to absorb water and salts from

partially digested food that enters from the small bowel and then

send waste out of the body through the anus. What remains after

absorption is stool, which passes from the colon into the rectum

and out through the anus when a person has a bowel movement.

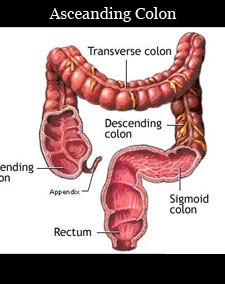

The colon comprises several segments:

* the cecum, the portion just after the small bowel

* the ascending colon

* the transverse colon

* the descending colon

* the sigmoid colon, an S-shaped portion near the end of the colon

* the rectum, where stool is stored until evacuation

The colon is formed during the first 3 months of embryonic

development. As the bowel lengthens, part of it passes into the

umbilical cord, which connects the fetus to the mother. As the

fetus grows and the abdominal cavity enlarges, the bowel returns

to the abdomen and turns, or rotates, counterclockwise to its

final position. The small bowel and colon are held in position by

tissue known as the mesentery. The ascending colon and descending

colon are fixed in place in the abdominal cavity. The cecum,

transverse colon, and sigmoid colon are suspended from the back of

the abdominal wall by the mesentery.

Anatomic Problems of the Colon

Malrotation and Volvulus

If the bowel does not rotate completely during embryonic

development, problems can occur. This condition is called

malrotation. Normally, the cecum is located in the lower right

part of the abdomen. If the cecum is not positioned correctly, the

bands of thin tissue that normally hold it in place may cross over

and block part of the small bowel.

Also, if the small bowel and colon have not rotated properly, the

mesentery may be only narrowly attached to the back of the

abdominal cavity. This narrow attachment can lead to a mobile or

floppy bowel that is prone to twisting, a disorder called volvulus.

(See the section on volvulus.)

Malrotation is also associated with other gastrointestinal (GI)

conditions, including Hirschsprung disease and bowel atresia.

Malrotation is usually identified in infants. About 60 percent of

these cases are found in the first month of life. Malrotation

affects both boys and girls, although boys are more often

diagnosed in infancy.

The colon is held in place by the mesentery

In malrotation, the cecum is not positioned correctly. The tissue

that normally holds it in place may cross over and block part of

the small bowel.

In infants, the main symptom of malrotation is vomiting bile. Bile

is a greenish-yellow digestive fluid made by the liver and stored

in the gallbladder. Symptoms of malrotation with volvulus in older

children include vomiting (but not necessarily vomiting bile),

abdominal pain, diarrhea, constipation, bloody stools, rectal

bleeding, or failure to thrive

Various imaging studies are used to diagnose malrotation:

* x rays to determine whether there is a blockage. In malrotation,

abdominal x rays commonly show that air, which normally passes

through the entire digestive tract, has become trapped. The

trapped air creates an enlarged, air-filled stomach and upper

small bowel, with little or no air in the rest of the small bowel

or the colon.

* upper GI series to locate the point of intestinal obstruction.

With this test, the patient swallows barium to coat the stomach

and small bowel before x rays are taken. Barium makes the organs

visible on x ray and indicates the point of the obstruction. This

test cannot be done if the patient is vomiting.

* lower GI series to determine the position of the colon. For this

test, a barium enema is given while x rays are taken. The barium

makes the colon visible so the position of the cecum can be

determined.

*computed tomography (CT) scan to help determine and locate the

intestinal obstruction.

Malrotation in infants is a medical emergency that usually

requires immediate surgery. Surgery may involve

* untwisting the colon

* dividing the bands of tissue that obstruct the small bowel

* repositioning the small bowel and colon

* removing the appendix

Surgery to relieve the blockage of the small bowel is usually

successful and allows the digestive system to function normally.

Small Bowel and Colonic Intussusception

Intussusception is a condition in which one section of the bowel

tunnels into an adjoining section, like a collapsible telescope.

Intussusception can occur in the colon, the small bowel, or

between the small bowel and colon. The result is a blocked small

bowel or colon.

Intussusception is rare in adults. Causes include

* benign or malignant growths

* adhesions (scarlike tissue)

* surgical scars in the small bowel or colon

* motility disorders (problems with the movement of food through

the digestive tract)

* long-term diarrhea

Some cases of intussusception have been associated with viral

infections and in patients living with AIDS. It can also occur

without any known cause (idiopathic).

In infants and children, intussusception involving the small bowel

alone, or the small bowel and the colon, is one of the most common

causes of intestinal obstruction. Malrotation is a risk factor.

Intussusception affects boys more often than girls, with most

cases happening at 5 months and at 3 years of age. Most cases in

children have no known cause, but viral infections or a growth in

the small bowel or colon may trigger the condition. In the past,

cases of intussusception appeared to be associated with a

childhood vaccine for rotavirus, a common cause of gastroenteritis

(intestinal infection). That vaccine is no longer given.

In adults with intussusception, symptoms can last a long time

(chronic symptoms) or they can come and go (intermittent

symptoms). The symptoms will depend on the location of the

intussusception. They may include

* changes in bowel habits

* urgency—needing to have a bowel movement immediately

* rectal bleeding

* chronic or intermittent crampy abdominal pain

* pain in a specific area of the abdomen

* abdominal distention

* nausea and vomiting

Children with intussusception may experience

* intermittent abdominal pain

* bowel movements that are mixed with blood and mucus

* abdominal distention or a lump in the abdomen

* vomiting bile

* diarrhea

* fever

* dehydration

* lethargy

* shock (low blood pressure, increased heart rate requiring

immediate attention)

If intussusception is not diagnosed promptly, especially in

children, it can cause serious damage to the portion of the bowel

that is unable to get its normal blood supply. A range of

diagnostic tests may be required. X rays of the abdomen may

suggest a bowel obstruction (blockage). Upper and lower GI series

will locate the intussusception and show the telescoping. CT scans

can also help with the diagnosis. When intussusception is

suspected, an air or barium enema can often help correct the

problem by pushing the telescoped section of bowel into its proper

position.

Both adults and children may require surgery to straighten or

remove the involved section of bowel. The outcome of this surgery

depends on the stage of the intussusception at diagnosis and the

underlying cause. With early treatment, the outcome is generally

excellent. In some cases, usually in children, intussusception may

be temporary and reverse on its own. If no underlying cause is

found in these cases, no specific treatment is required.

Fistulas

A fistula is an abnormal passageway between two areas of the

digestive tract. An internal fistula occurs between two areas of

intestine or an area of intestine and another organ. An external

fistula occurs between the intestine and the outside of the body.

Both internal and external fistulas may be characterized by

abdominal pain and swelling. External fistulas may discharge pus

or intestinal contents. Internal fistulas can be associated with

diarrhea.

The most common types of fistulas develop around the anus, colon,

and small bowel. These types are

* ileosigmoid—occurs between the sigmoid colon and the end of the

small bowel, which is also called the ileum

* ileocecal—occurs between the ileum and cecum

* anorectal—occurs between the anal canal and the skin around the

anus

* anovaginal—occurs between the rectum and vagina

* colovesical—occurs between the colon and bladder

* cutaneous—occurs between the colon or small bowel and the

outside of the body

Fistulas can occur at any age. Some fistulas are congenital, which

means they occur during the development of a baby. They are seen

in infants and are more common in boys. Other fistulas develop

suddenly due to diseases or after trauma, surgery, or local

infection. A fistula can form when diseased or damaged tissue

comes into contact with other damaged or nondamaged tissue, as

seen in Crohn's disease (intestinal inflammation) and

diverticulitis. Childbirth can lead to fistulas between the rectum

and vagina in women.

External fistulas are found during a physical examination.

Internal fistulas can be seen by colonoscopy, upper and lower GI

series, or CT scan.

Fistulas may be treated by surgery to remove the portion of the

intestine causing the fistula, along with antibiotics to treat any

associated infection.

Colonic Atresia

Colonic atresia is a condition that occurs during embryonic

development in which the normal tubular shape of the colon in the

fetus is unexpectedly closed. This congenital abnormality may be

caused by incomplete development of the colon or the loss of blood

flow during its development. Colonic atresia is rare and may occur

with the more common small bowel atresia.

Infants with colonic atresia have no bowel movements, increasing

abdominal distention, and vomiting. X rays will show a dilated

colon above the obstruction, which can then be located using a

barium enema.

Surgery is necessary to open or remove the closed area and

re-connect the normal sections of the colon.

Volvulus

Volvulus refers to the twisting of a portion of the intestine

around itself or a stalk of mesentery tissue to cause an

obstruction. Volvulus occurs most frequently in the colon,

although the stomach and small bowel can also twist. The part of

the digestive system above the volvulus continues to function and

may swell as it fills with digested food, fluid, and gas. A

condition called strangulation develops if the mesentery of the

bowel is twisted so tightly that blood flow is cut off and the

tissue dies. This condition is called gangrene. Volvulus is a

surgical emergency because gangrene can develop quickly, cause a

hole in the wall of the bowel (perforation), and become

life-threatening.

In the colon, volvulus most often involves the cecum and sigmoid

segment. Sigmoid volvulus is more common than cecal volvulus.

Sigmoid Volvulus

The sigmoid is the last section of the colon. Two anatomic

differences can increase the risk of sigmoid volvulus. One is an

elongated or movable sigmoid colon that is unattached to the left

sidewall of the abdomen. Another is a narrow mesentery that allows

twisting at its base. Sigmoid volvulus, however, can occur even

without an anatomic abnormality.

Risk factors that can make a person more likely to have sigmoid

volvulus are Hirschsprung disease, intestinal pseudo-obstructions,

and megacolon (an enlarged colon). Adults, children, and infants

can all have sigmoid volvulus. It is more common in men than in

women, possibly because men have longer sigmoid colons. It is also

more common in people over age 60, in African Americans, and in

institutionalized individuals who are on medications for

psychiatric disorders. In addition, children with malrotation are

more likely to get sigmoid volvulus.

The symptoms can be acute (occur suddenly) and severe. They

include a bowel obstruction (commonly seen in infants), nausea,

vomiting, bloody stools, abdominal pain, constipation, and shock.

Other symptoms can develop more slowly but increase over time,

such as severe constipation, lack of passing gas, crampy abdominal

pain, and abdominal distention. A doctor may also hear increased

or decreased bowel sounds.

Several tests are used to diagnose sigmoid volvulus. X rays show a

dilated colon above the volvulus. Upper and lower GI series help

locate the point of obstruction and show whether malrotation of

the rest of the colon is present. A CT scan may be used to show

the degree of twisting and malrotation, and whether perforation

has occurred.

In most instances, a sigmoidoscope, a tube used to look into the

sigmoid colon and rectum, can be used to reach the site, untwist

the colon, and release the obstruction. However, if the colon is

found to be twisted very tightly or is twisted so tightly that

blood flow is cut off and the tissue is dead, immediate surgery

will be needed to correct the problem and, if possible, restore

the blood supply. Dead tissue will be removed during surgery, and

a portion of the colon may be removed as well—a procedure called a

resection. Sigmoid volvulus can recur after untwisting with the

sigmoidoscope, but resection eliminates the chance of recurrence.

Prompt diagnosis of sigmoid volvulus and appropriate treatment

generally lead to a good outcome.

Cecal Volvulus

Cecal volvulus is the twisting of the cecum and ascending segment

of the colon. Normally, the cecum and ascending colon are fixed to

the internal abdominal wall. If not, they can move and become

twisted. The main symptoms of cecal volvulus are crampy abdominal

pain and swelling that are sometimes associated with nausea and

vomiting.

In testing, x rays will show the cecum out of its normal place and

inflated with trapped air. The appendix may be filled with gas,

but little or no gas is seen in other parts of the colon. Upper

and lower GI series will locate the volvulus and the position of

the colon. A CT scan may show how tightly the volvulus is twisted.

A colonoscopy, which uses a small, flexible tube with a light and

a lens on the end to see the inside of the colon, can sometimes be

used to untwist the volvulus. If the cecum becomes gangrenous or

holes develop in it, surgery will be needed.

|